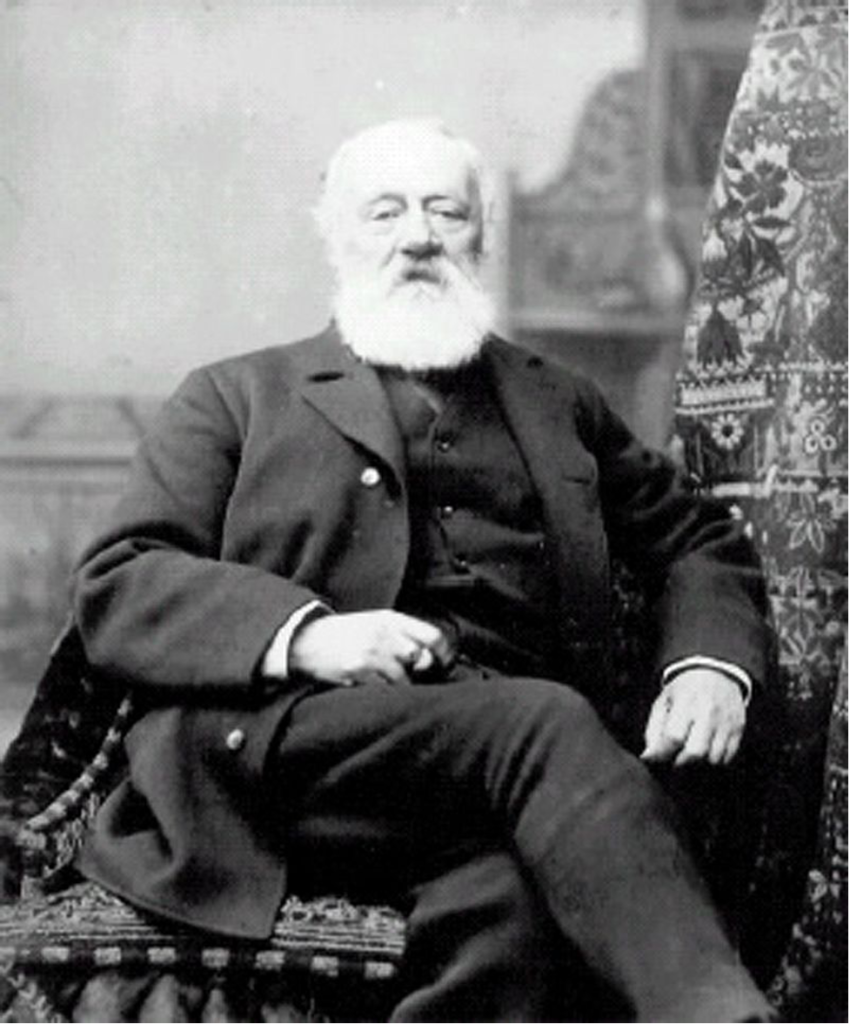

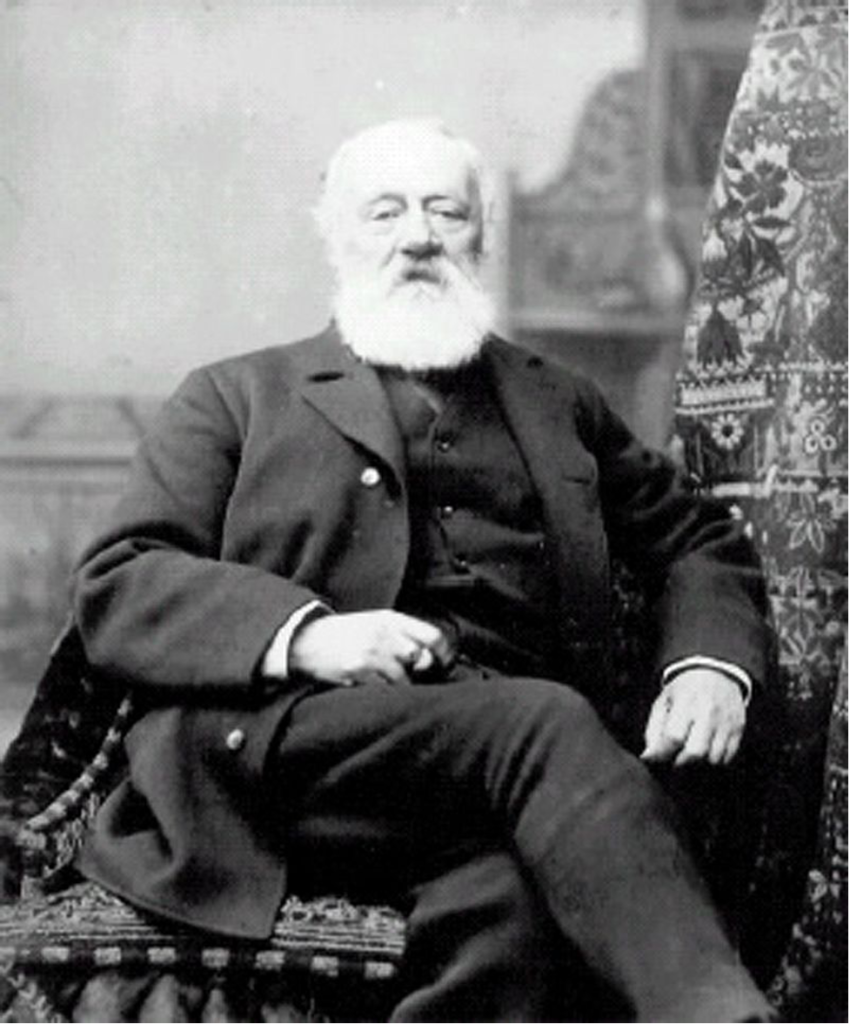

Antonio Meucci was a restless spirit. Born in 1808 in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, which, like much of Italy at the time, was under Napoleonic rule, he started working at the age of 15 as a customs officer at Porta Romana in Florence.

But even there, he made himself known by playing the role of a rebellious scientist with illegal fireworks. He ended up in prison and came into contact with some Carbonari.

Upon his release, he found work at the Teatro della Pergola as an assistant stagehand, but he couldn’t resist the temptation to express his political views. At the age of 23, inspired by the revolutionary movements of ’31 that were shaking Italy, he tore down the pictures of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany in front of the police. He was imprisoned for a second time, paying for his enthusiasm for republican and Mazzinian ideals. We like to remember him as a dreamer who wanted a united Italy and a radical social reform that would make it a more modern country.”

At that time, he was broke and in search of work. But he had a recognized skill and talent to rely on: appreciated at the Teatro della Pergola for inventing some communication mechanisms behind the scenes, he gained sympathy from the Italian impresario Alessandro Lanari, who recommended him to Don Francisco, another impresario who was assembling a company to go to Cuba. Being an adventurer, Antonio accepted the offer: on December 17, 1835, the Grand Italian Company disembarked in Havana. Meucci and his wife were in the front row. He initially worked at the Teatro de Tacon in the capital as the head stagehand.”

During those years, he gained fame and wealth and became involved in the world of medical electrotherapy, inventing a machine for treating rheumatism. Every experiment was conducted at his home. The news spread, and many people came to be treated, to the extent that his residence became known as the ‘house of health.’

But he was still a cursed man, and once again, business proved to be his Achilles’ heel: the theater caught fire, and he was left penniless. On May 1, 1850, to escape the unhealthy tropical climate for his wife Ester’s health and the risk of an anti-Spanish insurrection that seemed increasingly imminent in Havana, he moved with his wife to New York, specifically to Staten Island, a borough of the city.

He made himself known in the Italian community, which consisted mostly of political exiles. He associated with many compatriots, including Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Due to age differences, he could not have known Ferdinando Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists unjustly sentenced to death in America in 1927, but we like to imagine that if he had lived during their time, he would have sympathized with them.

He was not indifferent to what was happening around him, in short. He became passionate and involved: following Garibaldi’s example, he also joined the Masonic Lodge. And during these years, he designed his stearic candle. Not only that, he opened a factory to produce them in large quantities, providing employment to many Italian exiles, including Garibaldi.

Consistent with his previous tragic past, a fire destroyed the factory. At over fifty years old, he had to start from scratch. He didn’t speak English, his wife was ill, and the money he earned in Cuba was dwindling. He tried to convert the candle factory into a brewery, entrusting it to an American entrepreneur who ultimately left him destitute. Meanwhile, he immersed himself in new inventions, including patenting bleached paper made from wood, which attracted the interest of many newspapers at the time. But most importantly, he shaped the famous telettrofono, the predecessor of the telephone.”

He first experimented with it in 1854: he wanted to communicate with his wife, who was bedridden with rheumatism, while he was in the candle factory. Legend has it that she asked him, ‘Meucci, how are you? Do you want me to cook spaghetti for you?” And that he clearly heard her voice. The invention was inspired by a previous system he had created while working in the theater in Florence: a system of tubes that carried sound from one side of the stage to the other, to give instructions to the workers from the control booth.

On July 30, 1870, fate once again struck against him: the ferry he was traveling on between Staten Island and New York caught fire and sank. Meucci miraculously survived but was forced to stay in the hospital and then remain inactive for months. “As soon as he recovered, however, he created new devices. And in 1872, he attempted to patent the telettrofono: $250 was needed. He had only $20. Just enough for a caveat, a temporary patent to be renewed annually. He worked hard to find financiers in Italy but without success. He also presented the designs of his telettrofono to the vice president of the American District Telegraph Company in New York, the same company for which Alexander Graham Bell worked as a consultant, but the designs were lost. In 1874, he did not renew the caveat.” Two years later, Bell filed his patent.

It is unknown if Bell stole any information, certainly, throughout the 20th century, the invention was attributed to him. Yet, by the end of the 1880s, there were 50,000 telephones in the United States, and all the profits went to Bell’s company. Perhaps this is why the legal disputes began. In 1884, the Bell Telephone Company sued the Globe Telephone Company for patent infringement, as they marketed Meucci’s caveat. The court documents stated that the evidence spoke clearly: they argued that the words had been transmitted mechanically. Two months after that, Meucci died. But the subsequent verdict ruled in his favor.”

Only in 2002 did the United States Congress acknowledge, with unanimous approval of a resolution presented by Italian-American Congressman Vito Fossella of New York, that if Meucci had the funds, he would have patented the telephone. His rival, the American Bell, who took away his glory and success, and built an economic empire on the invention, emerged as a profiteer from that resolution.

It is a story with a bittersweet ending. While Alexander Graham Bell is often credited as the primary inventor of the telephone, Antonio Meucci’s work and his invention of the telettrofono undoubtedly played a significant role in the development of telecommunications technology. Meucci’s story serves as a reminder of the challenges faced by many inventors, the importance of recognition, and the complexities surrounding patent disputes and historical recognition.

Italian version

Antonio era uno spirito inquieto. Nato nel 1808 nel Granducato di Toscana, che, come gran parte dell’Italia dell’epoca, era sotto il dominio napoleonico, iniziò a lavorare all’età di 15 anni come doganiere a Porta Romana a Firenze.

Ma anche lì si fece conoscere interpretando il ruolo di un ribelle scienziato con fuochi d’artificio illegali. Finì in prigione e entrò in contatto con alcuni Carbonari.

Dopo essere stato rilasciato, trovò lavoro al Teatro della Pergola come assistente scenografo, ma non riuscì a resistere alla tentazione di esprimere le sue opinioni politiche. All’età di 23 anni, ispirato dai movimenti rivoluzionari del ’31 che scuotevano l’Italia, strappò i ritratti del Granduca Leopoldo II di Toscana di fronte alla polizia. Fu imprigionato per la seconda volta, pagando per il suo entusiasmo per gli ideali repubblicani e mazziniani. Ci piace ricordarlo come un sognatore che desiderava un’Italia unita e una riforma sociale radicale che la rendesse un paese più moderno.

In quel periodo, era senza soldi e in cerca di lavoro. Ma aveva una competenza riconosciuta e un talento su cui fare affidamento: apprezzato al Teatro della Pergola per aver inventato alcuni meccanismi di comunicazione dietro le quinte, guadagnò la simpatia dell’imprenditore italiano Alessandro Lanari, che lo raccomandò a Don Francisco, un altro impresario che stava formando una compagnia per andare a Cuba. Essendo un avventuriero, Antonio accettò l’offerta: il 17 dicembre 1835, la Grand Italian Company sbarcò a L’Avana. Meucci e sua moglie erano in prima fila. Inizialmente lavorò al Teatro de Tacon nella capitale come capo scenografo.

Durante quegli anni, guadagnò fama e ricchezza e si immerse nel mondo dell’elettroterapia medica, inventando una macchina per il trattamento del reumatismo. Ogni esperimento veniva condotto nella sua casa. La notizia si diffuse e molte persone vennero a farsi curare, tanto che la sua residenza divenne nota come la “casa della salute”.

Ma era ancora un uomo sfortunato, e ancora una volta gli affari si rivelarono il suo tallone d’Achille: il teatro prese fuoco e lui si ritrovò senza un soldo. Il 1º maggio 1850, per sfuggire al clima tropicale insalubre per la salute di sua moglie Ester e al rischio di una insurrezione antispanica sempre più imminente a L’Avana, si trasferì con sua moglie a New York, nello specifico a Staten Island, un distretto della città.

Si fece conoscere nella comunità italiana, composta principalmente da esuli politici. Si associò con molti connazionali, tra cui Giuseppe Garibaldi.

A causa delle differenze di età, non avrebbe potuto conoscere Ferdinando Nicola Sacco e Bartolomeo Vanzetti, due anarchici italiani condannati ingiustamente a morte in America nel 1927, ma ci piace immaginare che se avesse vissuto durante il loro tempo, avrebbe simpatizzato con loro.

Non era indifferente a ciò che accadeva intorno a lui, in breve. Diventò appassionato e coinvolto: seguendo l’esempio di Garibaldi, si unì anche alla Loggia Massonica. E durante questi anni, progettò la sua candela stearica. Non solo, aprì una fabbrica per produrle in grandi quantità, offrendo lavoro a molti esuli italiani, tra cui Garibaldi.

In linea con il suo passato tragico precedente, un incendio distrusse la fabbrica. A oltre cinquant’anni, dovette ricominciare da zero. Non parlava inglese, sua moglie era malata e i soldi che aveva guadagnato a Cuba si stavano esaurendo. Cercò di convertire la fabbrica di candele in una birreria, affidandola a un imprenditore americano che alla fine lo lasciò senza un soldo. Nel frattempo, si immerse in nuove invenzioni, tra cui il brevetto per la carta sbiancata ottenuta dal legno, che suscitò l’interesse di molti giornali dell’epoca. Ma, soprattutto, plasmò il famoso telettrofono, il predecessore del telefono.”

Lo sperimentò per la prima volta nel 1854: voleva comunicare con sua moglie, che era a letto con il reumatismo, mentre lui era nella fabbrica di candele. La leggenda narra che lei gli chiese: “Meucci, come stai? Vuoi che ti cucini degli spaghetti?” E che lui sentì chiaramente la sua voce. L’invenzione fu ispirata da un sistema precedente che aveva creato mentre lavorava al teatro di Firenze: un sistema di tubi che trasportava il suono da un lato del palcoscenico all’altro, per dare istruzioni agli addetti dal regista.

Il 30 luglio 1870, il destino si abbatté nuovamente su di lui: il traghetto su cui viaggiava tra Staten Island e New York prese fuoco e affondò. Meucci sopravvisse miracolosamente ma fu costretto a rimanere in ospedale e poi inattivo per mesi. “Appena si riprese, tuttavia, creò nuovi dispositivi. E nel 1872 cercò di brevettare il telettrofono: erano necessari 250 dollari. Aveva solo 20 dollari. Appena sufficienti per un avviso preliminare, un brevetto temporaneo da rinnovare annualmente. Lavorò duramente per trovare finanziatori in Italia, ma senza successo. Presentò anche i disegni del suo telettrofono al vicepresidente dell’American District Telegraph Company di New York, la stessa azienda per cui Alexander Graham Bell lavorava come consulente, ma i disegni andarono perduti. Nel 1874, non rinnovò l’avviso preliminare.” Due anni dopo, Bell presentò il suo brevetto.

Non si sa se Bell abbia rubato informazioni, certo, durante tutto il XX secolo, l’invenzione gli venne attribuita. Tuttavia, alla fine degli anni ’80 del XIX secolo, c’erano 50.000 telefoni negli Stati Uniti e tutti i profitti andavano alla società di Bell. Forse è per questo che nacquero le controversie legali. Nel 1884, la Bell Telephone Company intentò una causa alla Globe Telephone Company per violazione di brevetto, poiché commercializzavano l’avviso preliminare di Meucci. I documenti del tribunale affermavano che le prove parlavano chiaramente: sostenevano che le parole erano state trasmesse meccanicamente. Due mesi dopo, Meucci morì. Ma la successiva sentenza gli fu favorevole.”

Solo nel 2002 il Congresso degli Stati Uniti riconobbe, con l’approvazione unanime di una risoluzione presentata dal deputato italoamericano Vito Fossella di New York, che se Meucci avesse avuto i fondi, avrebbe brevettato il telefono. Il suo rivale, l’americano Bell, che gli tolse gloria e successo e costruì un impero economico sull’invenzione, emerse come un profitto da quella risoluzione.

È una storia con un finale agrodolce. Mentre Alexander Graham Bell è spesso accreditato come il principale inventore del telefono, il lavoro di Antonio Meucci e la sua invenzione del telettrofono hanno senza dubbio svolto un ruolo significativo nello sviluppo della tecnologia delle telecomunicazioni. La storia di Meucci serve come un promemoria delle sfide affrontate da molti inventori, dell’importanza del riconoscimento e delle complessità che circondano le controversie brevettuali e il riconoscimento storico.

Sign up to our mailing list to be the first to get notifications of contests, events and news.